A new adventure one year after Nandi Hills.

On the anniversary of our small adventure at the Nandi Hills, the five of us embarked on one more adventure. Our classmates, impressed by our maiden venture to the Nandi Hills, decided they wished to accompany us on weekend journeys. These trips included

women, and gained a corporate flavor, with vehicle and hotel reservations made in advance. The organizers planned everything: seating arrangements in the tempo, room allocation, meal planning, and the itinerary. I accompanied everyone on these trips because the bunch of us visited a few interesting places I may never have visited otherwise. Someday, when nostalgia sweeps over me, I will share the details of these trips.

A year after our maiden trip, we, the original five, embarked on another adventure. Once again, we failed to plan, or, should I confess, we refused to plan. We went to the bus station, got into a bus bound for somewhere, and left our fate in the hands of God. I had not converted to atheism but kept my ambivalence towards religion, priests, and scam artists who don holy garb.

The bus journey.

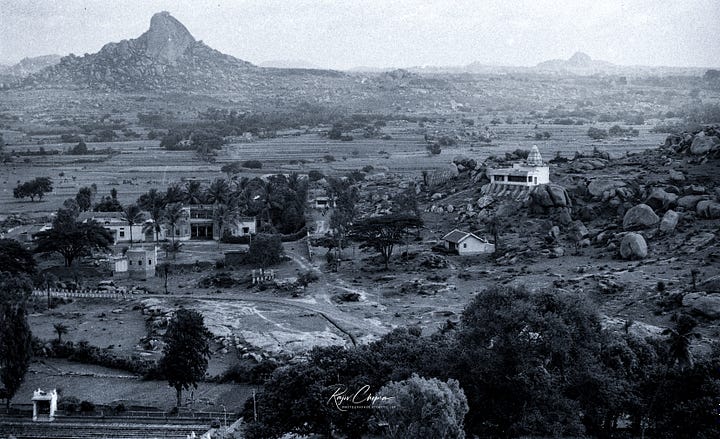

The rickety bus struggled to move along the highway. Buses didn’t have air-conditioning then, so we stuck our noses out of the window, breathing in the fresh country air. No one discussed pollution in those days, and dust was our only worry. The road was not dusty, the air was clean, and we stuck our snouts out of the window without fear. After an hour on the road, we noticed a huge rock rearing itself from the surrounding plains. The bus stopped, and we disembarked, walking towards the village, wondering if we’d find a decent hotel.

The priest’s home. The caste system affected me.

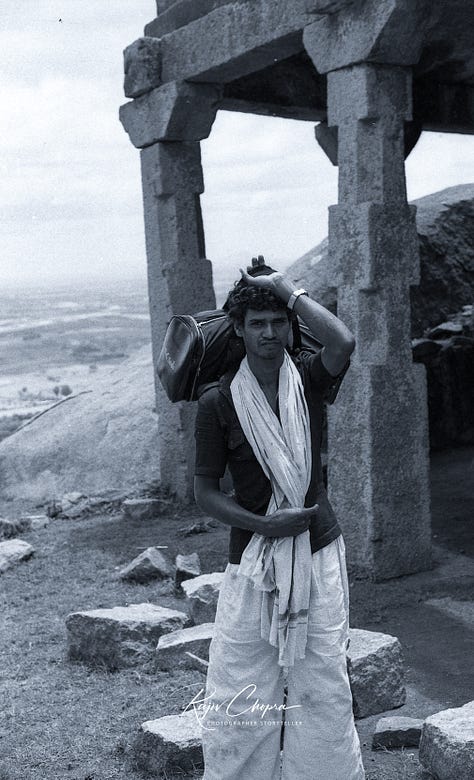

When we reached the village, we discovered the village didn’t have hotels or rest houses. Shivaganga (a villager told us the village’s name) was not on the tourist map. I don’t know if it was him or another villager who pointed us towards the local priest’s house. We entered, seeing a kind old couple in the house. When we asked if we could spend the night at his house, he asked us if all of us were Brahmins.

My companions beamed, nodding their heads, confirming their superior, Brahmanical status. I shook my head, refusing to lie about my caste. During my childhood, someone told me I am a Kshatriya, a member of the princely and warrior caste. I remember walking around with a puffed chest, chortling with relief about not being a priest! Only when I reached my teens did I begin questioning the rigid walls between people of different castes, shedding my early, simplistic view of caste barriers. A few years later, when I traveled to villages in North India, upper caste villagers told me they often refused water to Muslims or to those of a lower caste, especially the untouchables. Anyone who offered water to these people ensured that no one else in the house touched the utensils because they had become impure.

Much of this discovery lay in the future, but, I received a taste of caste discrimination that day when the priest refused to allow me to sleep in his house. Not wishing to abandon me to my fate, my classmates asked him if there was another place to spend the night. He allowed us the use of a small hut, which was his outhouse, on the condition that we were all Hindus. I affirmed my fast-vanishing Hindu faith, but I did not share my disgust. All of us wanted a roof to sleep under at night.

He blessed our souls and packed us off to his bare hut, which had nothing but a dusty floor. Mixed feelings ran through me that day, relief dominating the dull anger rising inside me. The anger grew over the following years, causing me to reject the present caste system, with its rigid walls, justification of discrimination, inherent cruelty, and inhumanity. These feelings remained latent for years, overshadowed that day by the pleasure of spending the night in a hut.

A drunken orgy, and a walk in the night.

Sitting on the floor, we opened the bottles, and were about to embark on our journey to being sozzled when one of our group members began yelling. He screamed, "Stop, we cannot drink here," overcome with regret and a prickly conscience. We will commit a sin by getting drunk on holy land.” It was a ridiculous situation, with just me opposing the plan to drink outside. I had no concerns for my non-Brahmanical soul, but, I held the lone minority voice.

After trudging up the hill, we found a grassy spot to sit on, with a rock to rest our backs, opened the bottles, and gave ourselves over to guilt-free drinking. Soon, too drunk to walk down to the hut, with a fleeting regret at losing our shelter, we settled into a steady snoring rhythm.It is possible we could have been an excellent rock band, with the rhythmic snored becoming our maiden hit!

We slept in a row, with me at the edge of the group. While I am immune to the cold, I can't withstand the pressure of a fat man pushing in the middle of the night. Rolling back and forth on the grass, I resembled a cylinder on slippery ground, with his voice like a foghorn in my ear. "Chops, Chops, Chops. Wake up! I am freezing!" Sure enough, a pleasant breeze was blowing, but it was nothing that could cause us to die of frost. Everyone woke up, rubbing their eyes, declaring they were freezing and stood at Death’s Door. We insisted on walking down to the hut. The path was clear, but we overlooked one obstacle: no one remembered the direction we came from and had to walk towards.

The situation demanded a hero: me. I stepped up and promised to lead them back to The Promised Land.

"I have excellent night vision," I said, “And, I will lead you back.” Unfortunately, I had not considered one minor obstacle: the effect of the booze had not worn off, making my head heavy and blurring my famed night vision.

After an hour of stumbling down the hill, groping for direction, we declared ourselves lost, too tired to walk further, and fell to the earth in deep slumber. The sun rose, as it does every day, and we discovered we were lying in a field, surrounded by cows being milked. The sloshing milk in the pails was unpleasant and served as a reminder of the risk of getting milk baths and cowherds chasing us. It was easy to find the priest’s hut in the morning, and we asked him how we could repay his hospitality.

Discovering Gotra, and bidding the priest farewell.

He offered to perform a small individual ceremony for each of us. I walked in first. The priest did not vocalize his thoughts, but I am convinced he wanted to dispose me off first, impure Kshatriya that I am. I squatted on the floor in front of him, and he asked me my ‘gotra.’ I looked around, and, not finding anyone, asked him what this strange thing–‘gotra’—was. Of course, I knew it was not an animal: I was in a priest’s home. Disgust filling his righteous frame as he gazed at me with contempt. Then, he performed a hurried ceremony and asked me for two rupees.

The priest’s wife took a shine to one of our group, and we observed her making eyes at him–the shameless woman! My friend’s ceremony was long, detailed, smoky, and cost him fifty rupees. Ignorance can save a person lots of money! In those days, fifty rupees were a fortune!

Gotra broadly refers to a patrilineal lineage. There are many beliefs. The most common is that we can all trace our lineage back to seven rishis, or sages, who were sons of Brahma, the creator God in the Hindu pantheon of (mainly) three gods.

Years later, when my father died, and the priest asked me about my gotra, I gave him the same blank look I gave the priest in Shivaganga. A crucial difference separated the two incidents. My uncle stepped in and declared we belonged to the ‘Kashyap’ gotra. I didn’t need to ask the latter priest a stupid question. So, I shrugged my shoulder and said to myself, “Hello Kashyap, nice to meet you.”

Atheism strengthens the soul, and I will stop here, lest I travel along an undesirable tangent about God and religion.

After consuming a shitty little breakfast, we began climbing the steep slope. I don’t remember where we ate, just that it was awful. We had awful meals right through our brief stay in Shivaganga and consoled ourselves with the thought that adventure motivated this trip, not food.

Climbing the Hill. God. The first step towards self-mastery.

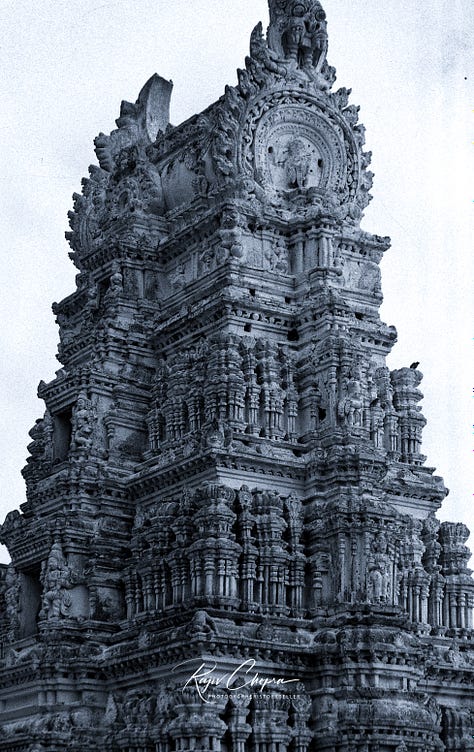

Even though I grew up in the hills, I’ve never liked steep slopes. Vertical drops make me giddy, making me conjure images of myself diving like a wounded swallow to the distant earth below. This slope was steep, with metal railings for us to cling to. Modern humans like to believe we are always scaling new pinnacles of technology, and our conviction is often correct. Yet we refuse to acknowledge the courage and capabilities of our ancestors.

When we reached the top, we circumambulated around a little statue on a rock. A metal pipe was our only foothold. We clung to the metal railing, praying we would not slip on the narrow metal foothold, remembering God when it suited us. Osho said fear drives a belief in God, and I agree. Yet, I don’t fully agree when he says fear drives people to believe in God. When I walked on that narrow piping, fear drove my temporary belief in God, but those who built temples on the pinnacle of steep, treacherous hilltops did so because of their faith in God. I don’t know if a connection exists between fear, faith and divine love, and I don’t wish to explore the subject. To each his or her own.

When I? reflect on the climb, I wonder what drove us five hungry, tired and hungover young men. Maybe it was our ego to prove we could climb without losing our nerves or breath. Or maybe curiosity impelled us forward, a desire to discover what was on top of the hill. The climb down was unpleasant for me, the plains stretching before me, inviting me to plunge headfirst in a fiery dive. I wanted to conquer my fear of steep slopes and made my first step towards self-mastery that day.

We often quote the Chinese proverb about a journey starting with a single step. The journey towards self-mastery is a journey with detours, thorns, barriers along the way. Self-mastery is a journey, not a destination, as I discovered in the years following our trip to Shivaganga. Yet, as my Chinese friends often remind me, we must take the first step.

The Famous Five go to Shivaganga